Fallen from its nest

- Details

- Category: Testimonies

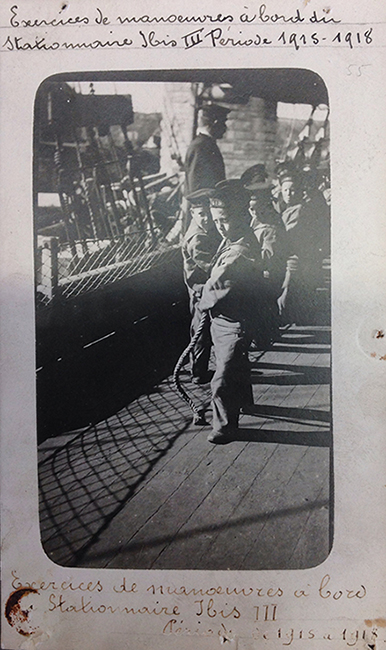

Many boys of the Ostend IBIS fishing school, the IBIS personnel and the IBIS director, fled to England too. They left on 13 October 1914 and stayed in the UK until the end of the war.

IBIS was founded by Prince Albert in 1906 and based at Sas-Slijkens (between Ostend and Bredene). Its aim was to improve access to education for fishermen orphans. For the majority of the fishing families poverty brought terrible living conditions at the end of the nineteenth century. Moreover, there was a shortage of highly-trained seafaring personnel. The boys lived on the IBIS training ship. They slept, ate and got lessons aboard.

In the early months of the war, the IBIS boys were actively involved in welcoming the many refugees who wanted to leave for England. They served as stretcher-bearers at the Red Cross first-aid post on the school premises. They helped wounded civilians, when Ostend was bombed at the end of September 1914. And they were helpful in preparing meals.

Preparations for setting course to England started on 8 October 1914. As Antwerp had already been occupied by the Germans and Ostend had become the temporary capital of Belgium, boys went home with their (visiting) parents on Sunday 11 October 1914. About 38 boys left the school on Sunday; 13 on Monday. 18 boys remained at school: either they were orphans or there was no place for them to go. Here are their names: The twin brothers Joseph and Walthere Gallé(13) and their younger brother Remy(10) The brothers Henri (12) and Julien Willeput (8), and the brothers Jules (10) and Victor Broucke (9) from Bredene Polidor Barbé (10), Arsène Hennaert (10), Arthur van den Stocken (9) Adriaan Dewitte (14) from Adinkerke, François van der Eynden (9) and Julien Goblet (9) Ferdinand Seys (14), Leon Rassaert (13), Robert Rogiest (11), Arthur Declerq (11) and Maurice Pattyn (11), all of them from Ostend

The logbook entry on 13 October 1914 shows everybody was making preparations for leaving Ostend. The orphans, the IBIS personnel and the IBIS director boarded the SS IBIS V and VI at 8.00 am, as well as 14-year-old Firmin Vandenberghe and his younger brother Achille (9), who had been taken home by their parents on Monday, but had returned on Tuesday. The latter boarded the SS IBIS VI. Initially, the IBIS VII stayed behind, but when the Germans marched into Ostend, it also set course for England, taking the IBIS warehouse workers and a group of refugees with it. The training ship had been requisitioned by the Belgian authorities.

“ The war was imminent then. The boys who had parents had to get off the ship, while the three of us could stay. As the German army was getting closer by the day and airplanes circled around above the ship one noon, we were all filled with a bit of panic, and nobody was allowed to board the ship without permission. The entrance was guarded by us day and night. I was a ten-year-old boy, marching in front of the entrance at night, with my rifle slung over my shoulder. Can you imagine how scared I was? Fortunately, it was but a few days. At the outbreak of the war, they cleaned a fishing boat of the IBIS fishing company as soon as possible, cleared the deck and the hold, put some tables in it and inserted hooks into the ceiling to hang hammocks. One day, we had to get our things together, put them in bag and hurry to the boat in Ostend. The next day we left for Milford Haven.” The IBIS community arrived at Folkestone on Wednesday morning. After having completed the legal formalities, they travelled to Milford Haven. The IBIS VI hold was being converted into an extra deck and a dormitory, while the children took up temporary residence in the Sailor’s Home during the renovation work. They could move to their floating accommodation as of 24 October 1914. A Belgian family, who also stayed in Milford Haven, agreed to do the laundry of the IBIS boys. An old sailor prepared their meals and was employed as a security guard. The large training ship IBIS III also managed to reach the harbour of Milford Haven on 23 November 1914. It was converted into floating accommodation too, with comfortable living rooms and dormitories. Renovation work was ready by January 1915. The boys were joined by ten youngsters from Adinkerke in 1917. Their fathers served in the army and King Albert himself intervened to settle the issue. In the early days of their stay in England, the director Prosper Wuylens found himself teaching. As of November, the children went to the local catholic school. And they also attended an after-school program that taught them the basic techniques of fishing. Since so many Belgian refugees had ended up in Milford Haven, the local authorities set up a Belgian school, i.e. the King Albert School for Belgians. The IBIS boys moved to that school, but things went far from smoothly sometimes. More than once, director Wuylens was notified of the naughty behaviour of some of the eldest IBIS children. Here is the letter Wuylens received from the English teacher John Brown on 17 December 1917:

Dear Mr Wuylens,

One of the boys of the Ibis was found to have tobacco and matches in his possession on Friday. Someone was smoking in the closet but I could not find out who. August Vanhove is the name of the boy. Yours faitfully, John Brown.

The director blamed the English boys for this behaviour. As of the schoolyear 1915-1916, the IBIS boys went to a ‘mixed’ school, with Belgian and English pupils and teachers. Remy Gallé attended that school too; as a result, it did not take long before he had quite a good command of English:

“We then had to choose a school. That was not so difficult, and we even had a Flemish teacher. The school was quite large and well equipped with folding doors to separate boys and girls. We were taught in English for one hour every day. It took us 15 minutes to reach the school premises. I studied very well and after almost a year I had quite a good command of English, which was also due to the fact that I played a lot with the English boys(sic). Also, I read a lot of books, which greatly enhanced my understanding of the English language.

Because I was so fluent in English, I was sent on errands to the shops. Everything was strictly rationed during the war. I was usually accompanied by two boys, and we carried a big sailcloth bag that held the products we bought. We went shopping in a large store. One day, I found a two-pound note on the floor and I immediately gave it to the boss master Louis. From that moment on, he always gave me a pack of chocolate biscuits when I went shopping. And we gladly accepted it, as we – young lads – were always hungry. For being sent on errands, the director paid me 1 shilling(2,50 Belgian francs) per month and 6 pence(1,25 Belgian francs) every Saturday. We usually went to the cinema on Saturday afternoon. We then received a pack of chocolate or 2 pence to buy ice cream. One day, when I got home from school with the other boys, I found a little bird. I guess it had tried to leave the nest before it could fly. I took it with me, gave it some bread(after having nibbled at it) and put it in a small box. It did not take very long before it could fly. I had fed it to the best of my abilities, it was really fond of me. When I came home from school, it flew towards me, begging for food, and I fed it, of course. It flew around the ship, and when we went to the lower deck to sleep, so did this little bird, nestling on one of the ropes of our hammock. One morning, however, I found it dead in a hammock. Crushed. I felt sad for several days after it had died. Never in my life had I known so much friendship and affection.”

The logbook and several personal letters show that the young refugees were doing relatively well in Milford: local craftsmen were helpful in renovating the ship, they completed their training course, the Belgian Refugees Aid Committee and the Ladies Committee of Milford Haven and South Wales handed out presents on holidays. Nevertheless, there was some animosity towards the Belgians from time to time. This is what Remy has to say about it: “Sometimes, the English did not behave in a friendly way towards the Belgians. Scuffles broke out at school, especially when the latter were celebrating something at school. Then, the English did not stop shouting “Belgians no good, stick ‘m up for firewood”. Fishermen who had gone too far on such occasions, were sent to Belgium and to the front.” Having had some reassurances they could have a safe journey back, the IBIS community – 27 boys - left for Ostend on 17 July 1919. The boat was also loaded with lots of fish, i.e. a present to the Ostend population from the Belgian ship owners in Milford Haven. The children could now ‘enjoy’ the summer vacation, before going back to school on 1 September 1919, as in the good old days.

Sources:

Ineke Steevens(scientific coordinator of the Fishing Museum in Oostduinkerke), Zeeslag (Sea battle), Vissers op de vlucht 1914-1918(Fishermen on the run). Lecture on ‘Contact Day’ ‘De Groote Vlucht’. Landbouw, Voeding en de Eerste Wereldoorlog, 10 October 2014, Miuuum, Roeselare.

http://www.ibisschool.be/index.php/algemeen/historiek.html

Thanks are due to Manon Dekien, trainee.